Critiques (1 078)

The Knick (2014) (série)

A medical series after the end of which you feel the need to wash off the drying blood and scrape the residue of a large intestine and placenta from under your fingernails. Soderbergh slowly and thoroughly draws us into a vortex of systematised madness and without regard for how many viewers will abandon the show after the first five minutes, when we’ll be doing cocaine with a racist misogynist, riding down a New York street where a black horse gasps in pain, and bearing witness to the death of a mother and her newborn child. ___ In addition to the music and natural (i.e. gloomy) lighting, Soderbergh’s cinematography is particularly helpful in inducing a feeling of nausea and the impression of a time and place where death is always just a step away and where you definitely would not want to end up with any illness more serious than a cold. The camerawork becomes more agitated along with the characters and transitions from clearly arranged, carefully composed shots giving the butchery on the operating table a hint of being civilised to immediate fly-on-the-wall observation and visceral, manually filmed close-ups. The fluidity of the narrative and the impression of a constant flow of events are aided by the “relay” observation of the characters, when the camera’s attention shifts from one actor and smoothly continues with another actor in the same shot. ___ The hospital is a complex organism whose problem-free operation requires the coordination of several notional tentacles and the taming of the egos for which the characters fight first and foremost rather than for their patient’s lives. While Thackery chooses cocaine to take the edge off and Barrow visits brothels, Edwards compensates for his inability to publicly fulfil his masculine role by engaging in self-destructive brawls like the protagonists of Fight Club. Most of the characters are connected by a theme that runs in various forms through Soderbergh’s filmography – the inability or impossibility to fit into the world in which they live and the associated emotional emptiness and feelings of alienation and loneliness. Thanks to the diversity of the individual characters and the conflicts that arise between them (while Thackery directly challenges God), Soderbergh’s dissection of a morally corrupt society succeeds in covering a broad range of issues, such as racial segregation, social stratification, the intertwining of class and racial tensions, corruption, migration, drugs and the church. With its effort to maintain a balanced distribution of attention, The Knick is akin to the more documentary-style untangling of complex webs known from the works of David Simon (The Wire, Treme). ___ The fourth episode, in which the central characters go hard at each other in games started previously, is comparably as dynamic as the pilot. However, not as much happens or as quickly, and what gives the episode its dynamism are primarily the constant changes in perspective, a Soderbergh trademark that superbly utilises varying depth of field. None of the many conflicting perspectives is privileged, which corresponds to the creators’ effort not to judge anyone and to show – with a clinical view and without embellishment or prejudice – that scientific and technical development was bought at the cost of devaluation of interpersonal relationships into mere business a century ago (techno-fetishistic details of every imaginable patent are increasingly available). 90%

Birth of the Living Dead (2013)

A slightly more ambitious making-of documentary recapitulating how a group of amateurs shot one of the first intentionally socially critical horror movies on a farm outside of Pittsburgh. Instead of behind-the-scenes photos and videos, the talking heads, shots from the completed film and news footage are complemented with comic-bookishly stylised animation that reinforces the guerrilla nature of the production at the time. A larger part of the documentary comprises a shot-by-shot breakdown of the film, particularly from sociological perspectives. The significance of the plot’s racial aspect is overstated, especially in light of the oft-repeated fact that the screenplay originally did not call for a black actor in the lead role. On the other hand, only a few sentences are dedicated to the raw style of the film, whose use of documentary aesthetics was one of the defining characteristics of the work done by the period’s rising generation of directorial rebels. The makers of this documentary nonsensically see the legacy of Night of the Living Dead in perhaps every American action movie of the 1970s, while ignoring the film’s more essential influence on horror titles not only in the United States, but also in Spain and Italy. For a sufficiently critical viewer who refuses to accept this misleading enthusiast perspective (films shot on location with strong black characters were definitely made earlier; see, for example, Shadows), Birth of the Living Dead can still be a satisfactory mapping of a singular phenomenon, despite the reservations detailed above. Let’s hope that it will also be the last such mapping, because there are many more films made in the US at the end of the 1960s that deserve an equally thorough media autopsy. 70%

Magic in the Moonlight (2014)

This review contains spoilers. I did not expect a lot of originality from the 78-year-old director’s forty-fifth film. Unfortunately, Woody Allen does even make an attempt at originality here and only dusts off previously used motifs: an older man in love with a younger woman (Manhattan, Whatever Works), communication with the dead (Alice), the importance of self-deception and faith in illusions (The Purple Rose of Cairo), and magicians, illusionists and hucksters (The Curse of the Jade Scorpion, Scoop). The initial premise would well serve one of Allen’s literary stories, but in a feature-length film, it runs out of steam after the first half-hour. Instead of further developing the plot, the next thirty-plus minutes are spent watching two or more people driving slowly or carrying on a static dialogue about death, God and love beyond the grave. Due to the poorly motivated final twist (which doesn’t explain how Catledge was involved in the whole game), the film is not only misanthropic, but also misogynistic. The complaining and caustic – though thanks to Firth, also charming – boor is given the truth so that he can remain who he is. Conversely, we have no reason to admire his victim, whom he spends a large part of the film trying to prove is a liar (a parallel with Allen’s personal life?). A young and naïve con-woman suddenly appears before us and she incomprehensibly submits to the malicious aging cynic rather than to the young, virile and wealthy ukulele player (judging from the rising popularity of that instrument, I’m guessing that Allen is using Brice as a means of mocking today’s youth and passing fads). The only explanation for her decision in the final scene is Allen’s wish for things to be just like this, for beautiful “manic pixie dream girls” to submit to intolerably sarcastic intellectuals who refuse to change their behaviour in any way. It seems that Sophie’s only reward for helping Stanley to get his second wind is a daily reminder of her intellectual inferiority. Other than a few jokes, whose punchlines Allen’s fans will see coming from a mile away, and two irresistible actors, this defence of love between an older man and a significantly younger woman offers nothing more than a sophisticated visual aspect. However, the fact that the often audaciously long shots of the French Riviera and elegantly dressed actors were captured on wide-screen 35 mm film loses significance in cinemas with digital projectors, i.e. the vast majority of them. Appendix: Immediately after the screening, I felt this was worthy of two stars. This evening, however, I saw Menzel’s The Don Juans and realised that an old man being in love with his own ego can take a far more monstrous form. 55%

Ray Harryhausen - Le titan des effets spéciaux (2011)

There’s no lingering on biographical facts here. The obvious purpose of this tech-nerd documentary is to expose younger viewers to Ray Harryhausen’s influence on the work of modern special-effects magicians, and to thus also to defend CGI as a noble continuation of the tradition. Though the speakers lack critical distance, their admiration is mostly for how convincingly a given monster moved, rather than for what a great guy Ray is. Like a number of other documentary portraits, this film becomes exceedingly sentimental in the closing minutes (Ray’s 90th birthday celebration). It’s intimated only subtly between the lines that the films with Harryhausen’s effects had mediocre screenplays and wooden actors, and that – with a few exceptions – watching them from start to finish would not be nearly as entertaining as this cherry-picked exhibition of the best trick scenes. In the case of such a fannish tribute (for example, the titles with the names of the speakers are complemented with miniature examples of their creativity) that could bear the subtitle “The Best of Ray Harryhausen”, such one-sidedness is understandable and probably unavoidable to a certain extent (try enticing Cameron, Jackson or Spielberg to take part in a film aimed at dispassionately assessing Ray Harryhausen’s life and work without concealing unpleasant truths). 80%

Vampyr (1932)

Dreyer’s admitted intention was to shoot a film the likes of which had never been made before. I would say that he succeeded. It would be too easy and not very accurate to describe The Vampire as a horror movie. I prefer the more vague classification “unsettling film”. It is unsettling in a way similar to how the films of Luis Buñuel and David Lynch are unsettling, as they are only tenuously anchored in reality. With repeated viewing, the initial astonishment turns into admiration for the formalistic sophistication with which the unnerving effect is achieved (and which may have been the reason that Alfred Hitchcock liked the film). The shots do not logically follow each other, the cuts are subordinate to the atmosphere rather than to the logic of the narrative, the asymmetrical shot compositions and confusing, avant-garde creative directions inspired by the structure of the space force us to constantly reassess where we are and whether this is reality, fantasy or a bad dream. The difficulty of differentiating objective and subjective shots is connected with the blurred lines between the real and the fantastical. One of the techniques that Dreyer used to violate standard narrative conventions and circumvent expectations is the independence of the camera. For example, in one scene the camera creates the impression that it is moving in accordance with the protagonist’s gaze, but it soon turns out that the protagonist is at the opposite end of the room with his back turned to the camera. This logically raises the disturbing question of who is standing behind the camera at that moment and who is watching. The intense feeling of unease that the film evokes is also due to the fact that it was shot in real conditions and the sounds were recorded afterwards, which forced Dreyer to evoke the terrifying mood primarily by visual means. Thanks to that, The Vampire has aged much more slowly than the first horror movies with full sound. In fact, it seems not to have aged at all. 90%

Les Gardiens de la Galaxie (2014)

Guardians of the Galaxy is terribly silly – a multifarious group of sociopaths race to find a silver orb in order to prevent cosmic genocide – but it’s also hard to resist. It is a heroic interplanetary adventure mixed with an ironic B-movie space opera that is nevertheless more serious and less bizarre than you would expect from a former Troma collaborator (Gunn is the co-author of the screenplay for Tromeo and Juliet and the book All I Need to Know About Filmmaking I Learned from the Toxic Avenger). ___ It’s rather unlikely that such a disparate group would come together, so we spend the whole film being persuaded that they can actually work together as a team. The development of the characters is limited to the transformation of hard-headed individualists into team players, which is skilfully incorporated into the main storyline – the plan has to be changed on the fly multiple times because the characters dumbly pursue their own objectives and complicate or delay the achievement of the main goal (Groot in prison, Drax on Knowhere). The film rather straightforwardly focuses on a group of outsiders being accepted by the system (which is dialectically represented by the peace-loving democratic planet Xandar and the Nova Corps military organisation), finding kindred spirits and becoming members of a notional new family (a large, live tree becomes its symbol in probably the most sentimental scene of the film). ___ However, it’s also essentially true that the deeper you go beneath the surface of the film, the more likely you are to be disappointed. The action scenes are spectacular, quite well arranged and sufficiently funny, but they don’t always serve the narrative. For example, the struggle after the first attempt to sell the orb didn’t have to happen at all or could have taken just a few tens of seconds and the impact on the main storyline would have been the same. Furthermore, the formula of “intergalactic terrorist wants to destroy/dominate the universe using a super-powerful artifact (which is nothing more than a MacGuffin)” is already rather worn out and the film doesn’t manage to overcome its clichéd nature quite as effectively as, for example, Iron Man 3 did. ___ On the other hand, it’s been a long time since I’ve seen a blockbuster that was such a joy to watch for its visual aspect alone – and often only for that. Whereas the plot, an Oedipal narrative in its most traditional form, is strikingly reminiscent of A New Hope (a young man growing up without his parents and whose father turns out to be a rather dark character is drawn into an adventure in which millions of lives are at stake) and cheap Star Wars imitations like Battle Beyond the Stars, The Ice Pirates and The Last Starfighter (whose posters obviously inspired the Guardians of the Galaxy poster), the visual creativity of the artists was clearly inspired by the kitschy scenography of the new Star Wars trilogy, the dark visions of H.R. Giger (a planet in a huge head) and the camp aesthetics of Flash Gordon. ___ In addition to the breathtaking visuals, which we can thoroughly enjoy thanks to the longer shots and the large number of deeply composed scenes and half-scenes (which, among other things, serve to illustrate the motif of team cohesion, or lack thereof), Guardians of the Galaxy is notable for its parallel targeting at multiple age groups. Unlike other self-conscious genre pastiches, it doesn’t offer greater pleasure only for those viewers who are familiar with the various fictional worlds (Star Trek, Godzilla, Django), but also for viewers who are familiar with various frames of reference, particularly the present day and the 1980s in this case. Quill represents this duality in the diegesis. On the one hand, he easily fits in among contemporary nerdy heroes with their own system of values that is not derived from authorities, who care more about their technological toys (Walkman, mask) than about living beings and are walking encyclopaedias of pop culture. On the other hand, Quill is also a child of the ’80s, which is evident not only in the objects on his instrument panel (an old cassette recorder, a troll doll, an ALF sticker), but also in most of the films that he quotes from (Footloose, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Howard the Duck). The music that he listens to (naturally on a Walkman from the ’80s), which his absent mother recorded for him and which repeatedly interferes with the development of the narrative, can also be understood as a reminder of the period of his childhood, i.e. the ‘80s. If the 1980s, understood as a period of return to conservative values, serve as a model for the hero’s actions and thinking, this is a variation on the formula of Back to the Future, in which the ’80s had to be “corrected” according to the model of the innocent 1950s. What is implied by all of today’s looking back to the values represented by Reagan’s America of the 1980s? I’d prefer to let others answer that, but I don’t have a very good feeling about it. 80%

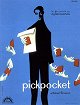

Pickpocket (1959)

The only thing he believed in was God. For three whole minutes. He now no longer believes. He doesn’t believe that he would interest anyone or that anyone would take him into consideration. Therefore, he steals. He feels that he is part of the indifferent world around him only when his hand, as if independent of the rest of his body, rummages through other people’s pockets. He belongs somewhere; he’s doing something. He is living...in the same mechanised substitute for life as everyone else. Just as in the case of the earlier A Man Escaped, it’s possible to imagine how Hollywood would have taken the plot of Pickpocket and turned it into a suspenseful thriller. Bresson chose the opposite route in the form of an elliptical narrative absolutely devoid of drama. There is no interest in the action, which is intentionally opaque and shot without excitement, like the rest of the film. The commentary, rationalised this time by Michel’s letter, is offered as the most convenient connection to the protagonist’s mental processes. However, we basically do not learn more from it than what we see for ourselves. Pickpocket isn’t exactly an accessible film (which is even more true of it than of Diary of a Country Priest and A Man Escaped). As such, however, it forces you to dig more deeply beneath the surface. It’s worth it for the feeling that you got close. 75%

Journal d'un curé de campagne (1951)

Like the book on which its based, this film does everything possible to ensure that we will not enjoy it. The narrator, a young man trying to hold on to his faith despite his own doubts and those of others, tells us through his diary (everything has been written down) what will happen and what we will see. All of the tension is built up inside of him, while he himself does not show any emotion, unlike the other, more lively characters – whether unbelievers or believers without the sincerity that the protagonist strives for. Through his untainted character without attributes, he offers a point of view, a grid through which we can interpret the film. Bresson’s minimalism doesn’t offer much room for further interpretation with only a few recurring settings, predominantly interiors, close-ups and the narrator’s voice. The priest is imprisoned in his own world and we with him. There are no superfluous shots, no distractions. An ascetic film. Painful, yet purifying. 80%

Až do mesta Aš (2012)

I admire the courage with which the young director and screenwriter wagered on veristic observation, but that’s where my respect for this film begins and ends. The raw style, which in places blurs the line between documentary and fiction (like the line between muted and no dramaturgy), serves the story, whose direction and (insipid) outcome will be figured out in advance by every viewer who has ever seen a social drama. The film isn’t fully polished in conceptual terms. The introspective animated sequences, fondly used in performative documentaries, clash with the unempathetic protagonist in the live-action scenes. The director’s attitude toward Dorota embarrassingly alternates between “she is to blame” and “others are to blame”. In this respect, Petr Václav’s The Way Out is more clearly and more impactfully expressive even at the cost of certain simplifications. With the exception of one unpleasant, though in no way explicit sex scene, the film does not let us experience the mange and filth into which the protagonist descends. As a statement on aimless adolescence, Made in Ash doesn’t come close to the Serbian film Clip or the Israeli Six Acts. In the context of Slovak-Czech cinema, it is a praiseworthy attempt at something different; in the context of contemporary festival dramas, it’s nothing new. 50%

Faust, une légende allemande (1926)

An example of German expressionism in all its glory. Monumental sets incorporated into the narrative, psychologising of the characters by means of expressive lighting, the actor’s body as a visual element that creates meaning, and strangely deformed set pieces serving to set the mood. Despite the advanced technical level, with the occasional somewhat exhibitionistic use of tricks, most of my attention was focused on Jannings’ Mephisto. He not only controls the fates of the characters, who – typically for expressionism – lose control over their own decision-making (the unforgettable scene in which Mephisto uses his cape as a theatre curtain), but also masterfully rules over the whole film with his lively eyebrows. He set a heretofore unsurpassed benchmark for assessing the charisma of cinematic devils. First by Kyser in pre-production, drawing from German fairy tales, and during production by Hoffman, drawing from the legacy of German romantic painting, romantic motifs were amplified beyond the scope of Goethe’s play, which is forcefully evident in the one-word climax, whose pathos is nothing to laugh at, as it fits seamlessly into the overall opulence of the film. Probably no one would have come up with a more universal and more urgent message and it is difficult to think of one today. Contemporary viewers would scorn such simplification in a modern epic. Here, however, the poetic point perfectly tops off a great story told in grand style. In my opinion, Murnau succeeded in his attempt to transform “home-grown” material into a global spectacle. 85%